When we think of genes, we usually imagine neat stretches of DNA lined up one after another like beads on a string. But nature, as it turns out, doesn’t always follow a tidy blueprint. In many organisms — including humans — some genes actually live inside other genes. These “nested genes” are located within the noncoding regions (introns) of larger “host” genes, sometimes even on the opposite DNA strand. This arrangement can create surprising levels of complexity, where two genes share the same piece of DNA but are read and regulated in very different ways. Scientists are still uncovering why this happens and how such intimate genomic neighborhoods influence gene expression, evolution, and disease.

These genomic arrangements arise through a variety of mechanisms, most commonly retrotransposition of processed mRNAs into introns of other genes, or through duplications and rearrangements that bring once-separate loci into close proximity. The orientation of the nested and host genes — either sense or antisense — can have major consequences for how they are regulated. Antisense configurations tend to be more stable, as they minimize transcriptional interference, while sense-oriented pairs often share promoters or enhancer elements, leading to coordinated or competitive transcription. Functionally, nested genes can influence their host’s transcription, splicing, and chromatin accessibility, or conversely be regulated by the host’s transcriptional activity. Such relationships have been implicated in diverse processes, from tissue-specific gene expression to genomic imprinting and disease-associated dysregulation. Overall, nested gene architecture exemplifies the intricate, multilayered nature of eukaryotic genome organization, where the same stretch of DNA can encode multiple, interdependent layers of information. Nested gene architectures are widespread across eukaryotic genomes, and their prevalence is particularly high among noncoding RNA genes. A large fraction of small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), and tRNAs are located within the introns of long noncoding or other RNA host genes — by some estimates, over half of human miRNAs and the majority of snoRNAs follow this pattern. In many cases, these intronic RNA genes are co-transcribed with their hosts and processed post-transcriptionally from the host pre-mRNA, linking their expression to host gene activity. This prevalence highlights that intronic RNA genes constitute the dominant form of genomic nesting, emphasizing the genome’s extensive reuse of intronic space for regulatory and functional diversification.

Nested protein-coding genes are relatively rare in the human genome, with estimates suggesting that only about 4–6% of protein-coding genes participate in intronic nesting. Their study is complicated by several caveats: many reported nested loci may represent poorly expressed or predicted genes, pseudogenes, or alternative transcripts rather than fully independent protein-coding units. Well-validated examples are thus limited, but one clear case is the STH (Saitohin) gene, which is entirely embedded within an intron of the MAPT (tau) gene. STH encodes a small protein of 128 amino acids and is transcribed independently of its host, illustrating that, although rare, nested protein-coding genes can maintain distinct expression and functional roles within a shared genomic locus.

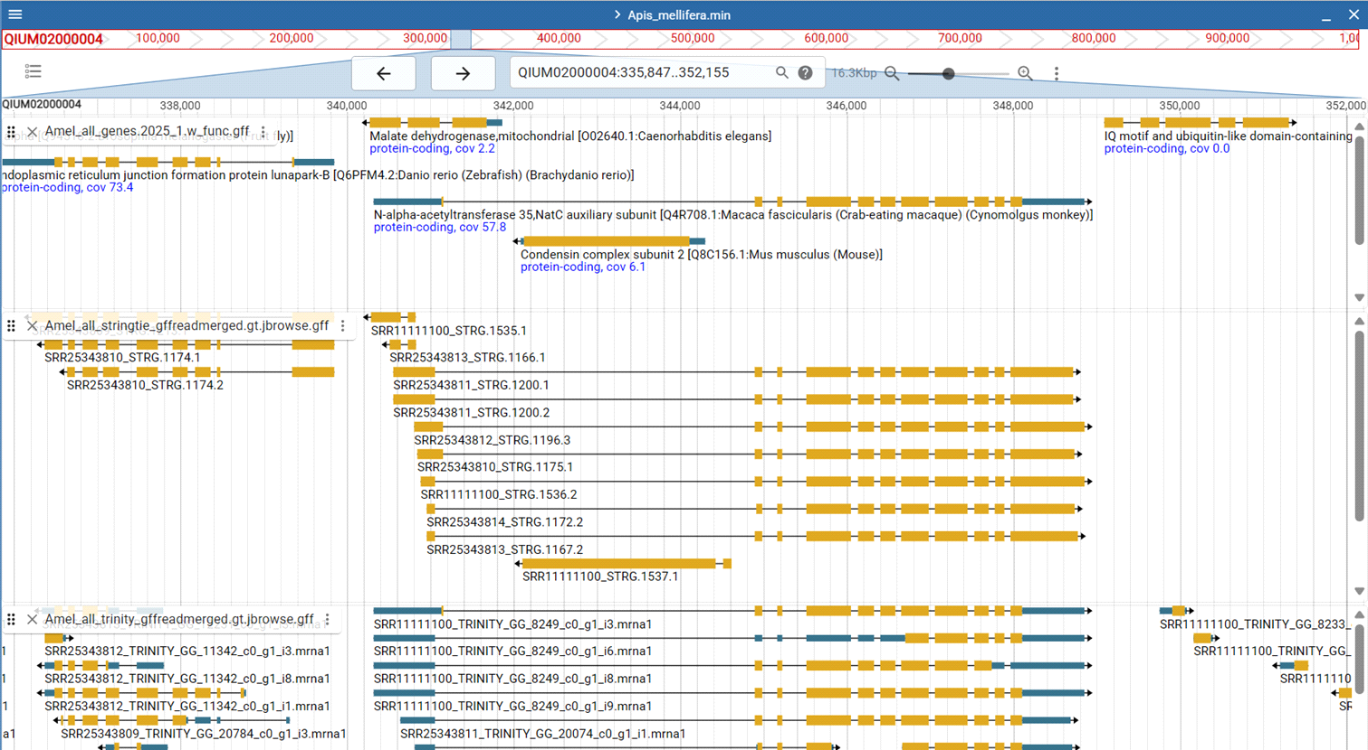

Identifying nested protein-coding genes is challenging due to limitations in transcriptomic and genomic evidence. Standard RNA-Seq mapping often struggles with reads that overlap host introns, particularly when strand specificity is not preserved, making it difficult to distinguish transcripts from the nested gene versus the host. Short reads may ambiguously map to multiple exons or shared repetitive sequences, and low expression of many nested genes further reduces detection sensitivity. These mapping ambiguities propagate into gene reconstruction algorithms, which rely on correctly assigned reads to define exons, introns, and splice junctions. As a result, many nested protein-coding genes are under-annotated or misassembled, and their transcriptional independence from the host can remain uncertain, complicating both functional annotation and prevalence estimates. The two screenshots from Apis mellifera annotation demonstrate these difficulties (upper track: genome annotation; middle track: StringTie gene reconstruction based on STAR generated read alignment; lower track: Trinity transcriptome assembly mapped onto the genome).