Functional annotation refers to the process of assigning biological significance to identified gene sequences. This involves inferring the functions of genes, transcripts, and proteins by aligning them with established databases, and detecting features such as protein-coding regions, functional domains, motifs, and gene ontology (GO) terms. It also encompasses the identification of regulatory elements, biological pathways, and molecular interactions, offering insights into the roles each gene plays in biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components.

In a previous post, we looked at the general challenge of assigning gene and protein names from existing databases with focus on the PANTHER system. PANTHER contains over 15,000 families and about 128,000 subfamilies, many of which inherit their names from early UniProt or GenBank entries. That’s why so many of these names include vague add-ons like “putative,” “related,” or “hypothetical,” and why some families don’t have proper names at all. These fuzzy labels flow straight into new genome annotations and often get even more watered down. As a result, the naming chains become unclear and can sometimes produce amusing or confusing entries.

Let’s look at the PANTHER “myosin” family PTHR13140 and compare it with the most recent comprehensive protein family study by Kollmar and Mühlhausen (2017, Myosin repertoire expansion coincides with eukaryotic diversification in the Mesoproterozoic era. BMC Evolutionary Biology 17, 211, 1-18). Myosins are motor proteins that move along actin filaments.

The muscle myosin heavy chain is the classic example, although other homologs have been well known and well described for decades, including the reverse-direction class-6 myosins, the vesicle-transporting class-5 myosins (which contain a DIL=dilute domain) and the membrane-remodelling class-1 myosins. The classification of myosins into distinct classes is well established and follows widely accepted principles. Classes are defined on the basis of phylogenetic trees built from motor-domain sequences. The node that marks a class must show very strong support, ideally 100 percent, and should correspond to the deepest possible node that is consistent with the species phylogeny. The decision whether neighbouring groups represent separate classes or simply variants of the same class is based on comparing their domain architectures. Fortunately, this distinction is always very clear, because ancient gene duplicates diverged rapidly and developed distinctly different domain architectures. In total, the most recent myosin classification identifies 80 classes, each defined by its unique domain architecture.

In PANTHER, subfamilies are defined based on phylogenetic relationships within a larger protein family. A phylogenetic tree is built for each family, reconstructing evolutionary events like gene duplication, speciation, or horizontal transfer. Subfamilies correspond to clades in that tree: new subfamilies are typically “founded” when a gene duplication or transfer event happens and one copy diverges rapidly in sequence. Curators (biologists) manually inspect these trees and define subtrees (subfamilies) that are functionally coherent, i.e., the members should share a similar name and biological function. Each subfamily gets its own Hidden Markov Model (HMM), built from the sequences in that subtree, so that new proteins can be classified into the correct subfamily. How does this definition apply to the myosin family? The current “classification” lists 90 myosin subfamilies, yet these subfamilies are scattered across the entire tree. In many cases they are interrupted by other subfamilies, and their members are often mixed with members of these other groups.

The core issue is that the underlying algorithms cannot reliably distinguish homologs, orthologs and paralogs. Plants, for example, contain myosins from only two classes, class-8 and class-11, each with several variants. If the annotations used as input for PANTHER’s tree calculations are incomplete, certain variants will be missing. This leads to incorrect speciation and duplication assignments. Wrong annotations, for instance missing exons or intronic regions mistakenly annotated as exons, further distort the tree and the variant assignments.

A second major problem that heavily compromises the myosin analysis is the use of full-length sequences. Myosin family trees are defined on the basis of the motor domain, not on the full-length proteins. Alignments of full-length sequences can be used, but only if they undergo extensive manual curation. The motor domain may sit at the N-terminus, in the middle or at the C-terminus. Automatic alignment tools cannot handle this variability and therefore end up aligning motor domains against tail domains and tail regions against entirely unrelated domain architectures. It makes no biological sense to align DIL domains of class-5 myosins with the tandem MyTH4–FERM domains of class-7 myosins, the RhoGAP domains of class-9 myosins or the chitin synthase domains of class-17 myosins. This misinterpretation of the myosin family creates subfamilies that group together completely unrelated myosins. For example, the plant-specific class-8 and class-11 families suddenly contain sequences from Apicomplexa, Stramenopiles and other distant lineages, and the same pattern appears in several other well-defined classes.

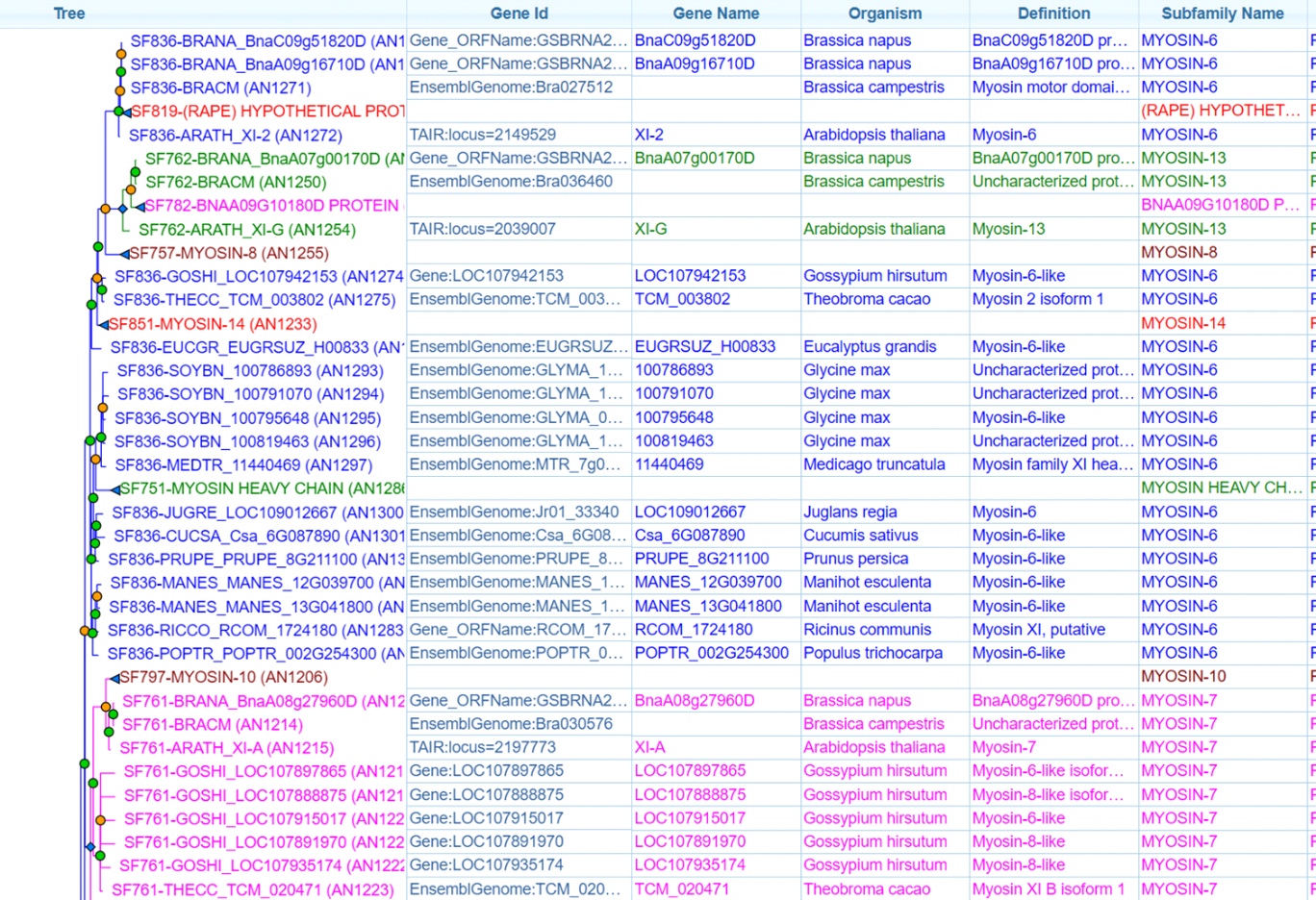

It is clear that PANTHER’s myosin tree has never been reviewed by an expert curator. Beyond the generally unusable classification, the introduction of new class names that do not exist in the scientific literature creates substantial confusion. For instance, some plant class-11 myosins are labelled “Myosin-6” or “Myosin-17.” Yet class-6 myosins are the well-known reverse-direction motors, and class-17 myosins are fungal myosins that contain a chitin-synthase domain. There is no evolutionary or functional relationship between these classes and any plant myosins. Assigning these incorrect PANTHER subfamily names to new genome annotations contaminates databases with large amounts of wrong information and misleads downstream experimental work.

Conclusion

The myosin family is only one example. Many other protein families show the same type of incorrect classification. Protein and gene names should never be assigned based on PANTHER subfamilies, because this only adds more incorrect and misleading annotations to public sequence databases.