The BUSCO completeness check assesses the completeness and quality of a genome, transcriptome or proteome assembly by searching for highly conserved single-copy orthologues that should be present in a given lineage. By providing datasets for specific taxonomic lineages, BUSCO helps assess evolutionary completeness. In previous parts I discussed some differences between the BUSCO completeness check of a genome assembly and the BUSCO completeness check of the genome annotation of that assembly, and showed examples of how artificially fused genes in the BUSCO data inflate completeness. Here, I will give you some insights into repeat sequences within BUSCO.

In genomics, the term “repeat” refers to both exact and imperfect repetitions of sequence motifs. Imperfect repeats are sequences that have undergone small variations or mutations. It is generally understood that roughly half of large genomes are composed of repeat regions, which include LINE and Alu elements, as well as various types of transposons and their relics. Some animal genomes even contain hundreds of thousands of tRNA-like elements, stretching the conventional definition of what constitutes a repeat. Sequence similarity among LINE elements or transposons can drop below 20%, which, by comparison, is roughly the lower limit often used to define protein sequence homology. Repeats are also common at the protein level, where many protein sequences and structures are built from recurring motifs such as WD40, ankyrin, or LRR repeats. While the analysis of imperfect repeats can become extremely complex and effectively open-ended, the study of exact repeats tends to be much more straightforward.

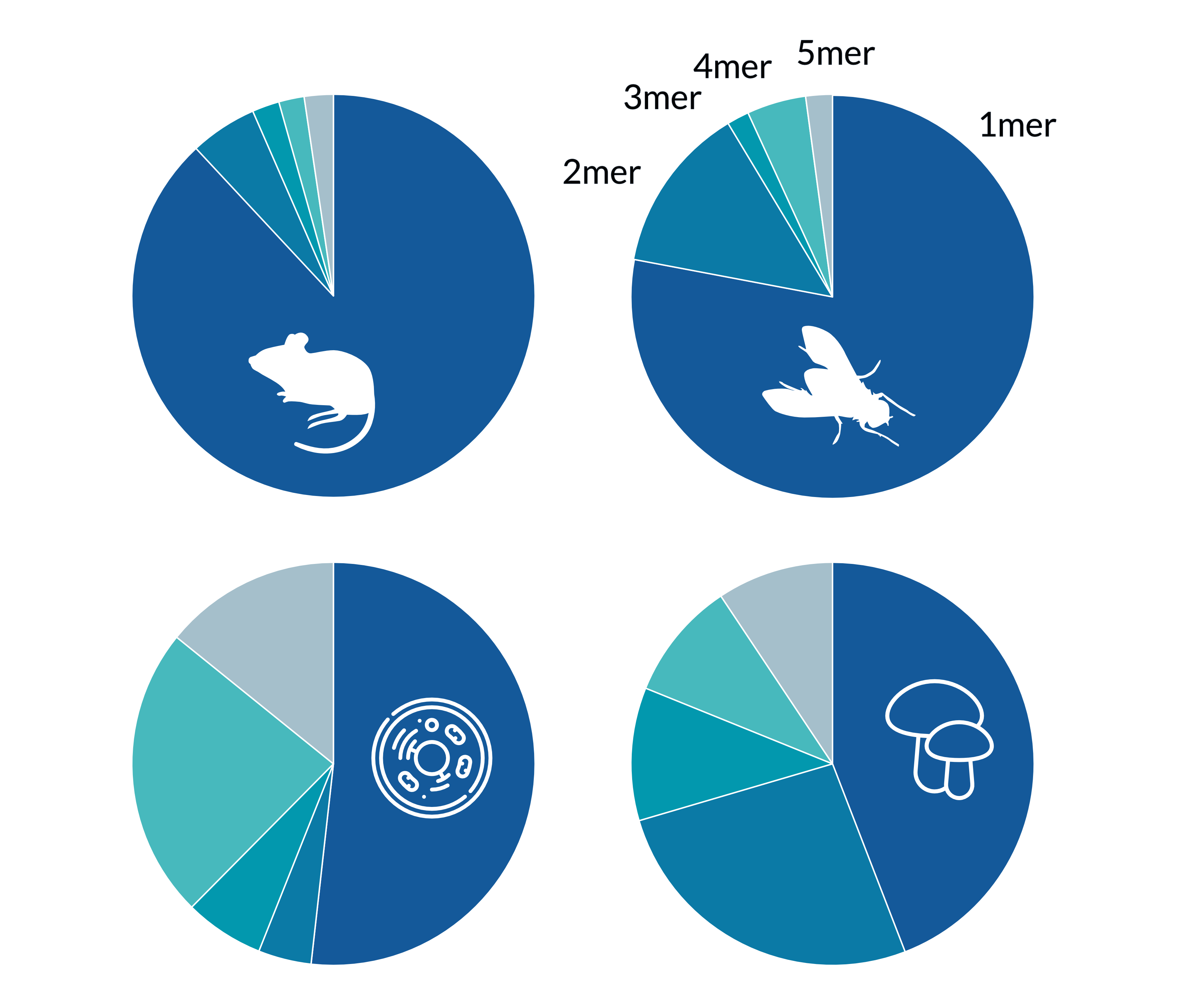

BUSCO relies on OrthoDB data, which in turn is built from publicly available protein sequences, most of which originate from gene predictions rather than experimentally verified proteins. Consequently, the extent of repeat regions in BUSCO datasets reflects, at least in part, issues in gene prediction for the corresponding species. We analyzed all eukaryotic BUSCO datasets for exact repeats composed of one to five amino acids, with a minimum repeat region length of 20 amino acids. For clarity, only representative examples from selected lineages are discussed here. Among animals, particularly within vertebrates and arthropods, we observed extensive repeat regions. For instance, 663 sequences (0.64%) in Carnivora and 1,579 sequences (0.75%) in Hymenoptera contained repeats. The Hymenoptera dataset showed especially pronounced examples, including single amino acid repeats—such as a stretch of 196 glutamates (E)—as well as longer motifs, such as a 204-amino-acid region composed of 51 tandem copies of the tetrapeptide “NGDR.” Such extreme repeat structures are highly unlikely to represent genuine protein sequences and are more plausibly artifacts of gene prediction errors, especially given the lack of homologous regions in related protein sequences. In contrast, fungal and protozoan datasets showed fewer single-amino-acid repeats, but relatively more complex repeat patterns involving longer motifs. There are even sequences in the BUSCO data consisting of only a single repeated amino acid.

Conclusion

Exact repeats do occur naturally in protein sequences; however, the extent and length of the repeats observed in the BUSCO data strongly suggest gene prediction artifacts rather than true biological features. Consequently, when trying to reach BUSCO genome assembly statistics with your own genome annotation, you are likely to incorporate erroneous or mispredicted gene regions into your analysis.